Welcome to the USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum’s Virtual Visit Portal

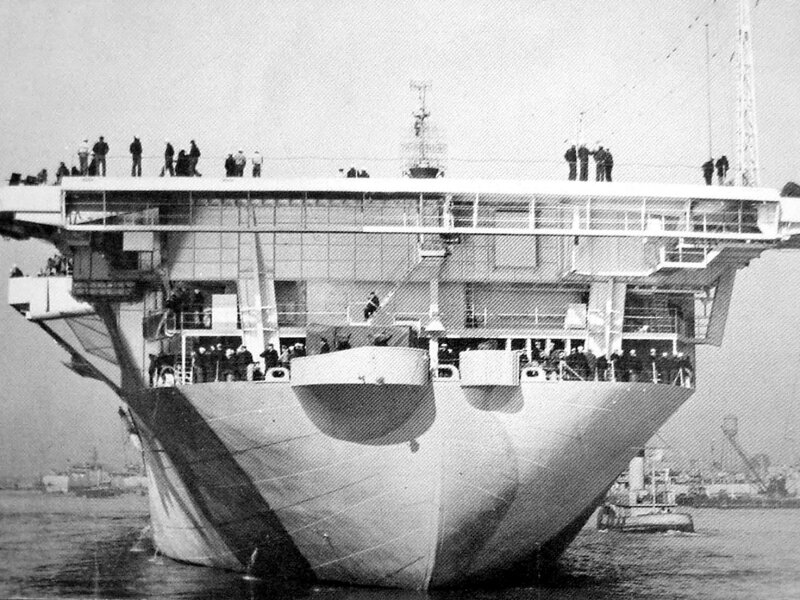

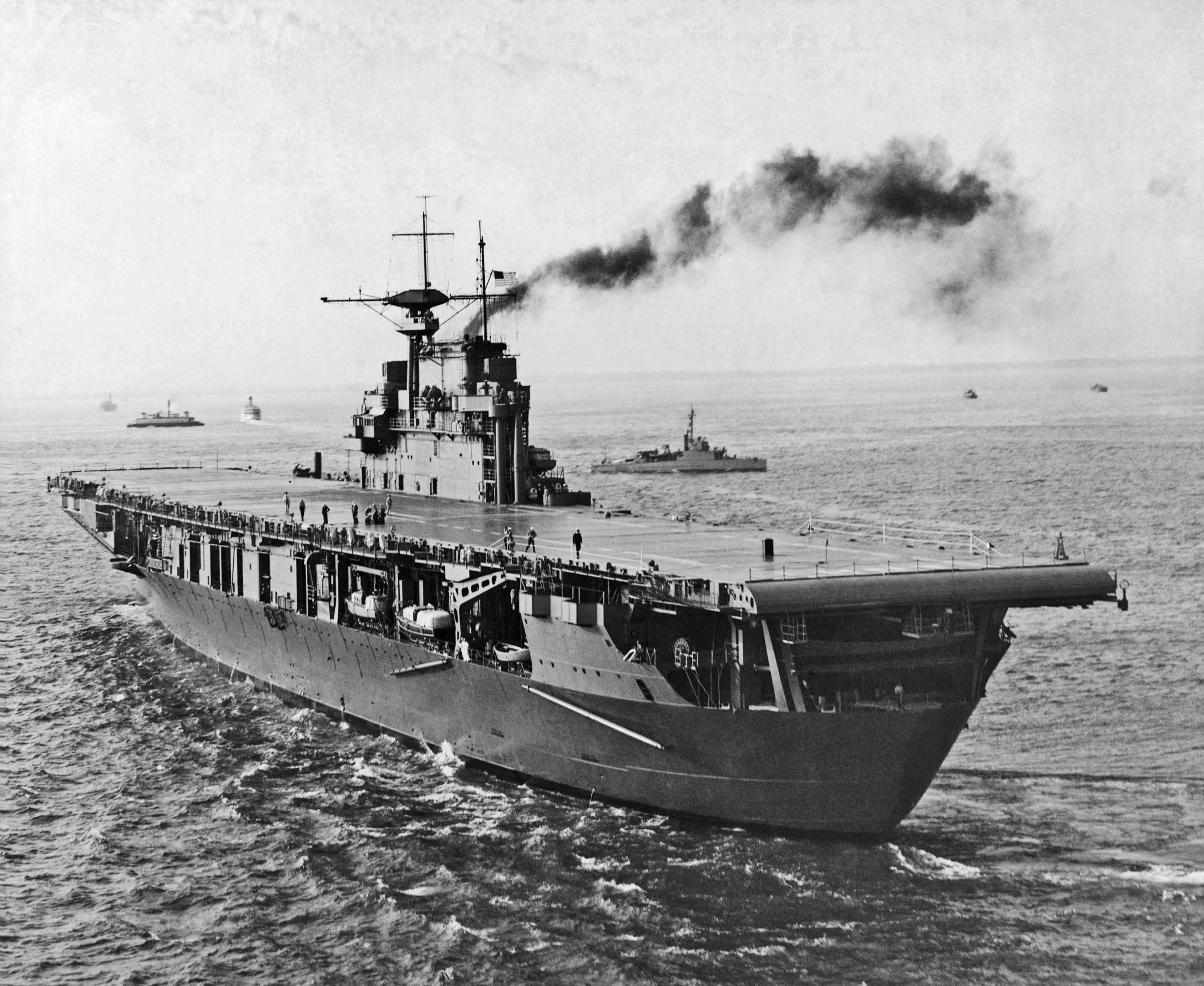

This page will guide you through our ship’s spaces, from the Bridge to the Engine Room. USS Hornet is an Essex-class aircraft carrier–at 894 feet long, 191 feet wide, and 19 decks tall, she’s about the same size as San Francisco’s iconic TransAmerica building turned on its side! While no longer the largest class of aircraft carrier on the high seas, touring the whole ship takes time.

We’re excited to share her with you and encourage you to also check out the “Things to Do” section on this page which includes additional activities and projects the Museum has created for programs and exhibits!

Want a Docent to take you on a virtual tour? Visit our Distance Learning Page for our Dialogue with a Docent Program! Click here or the button on the right!

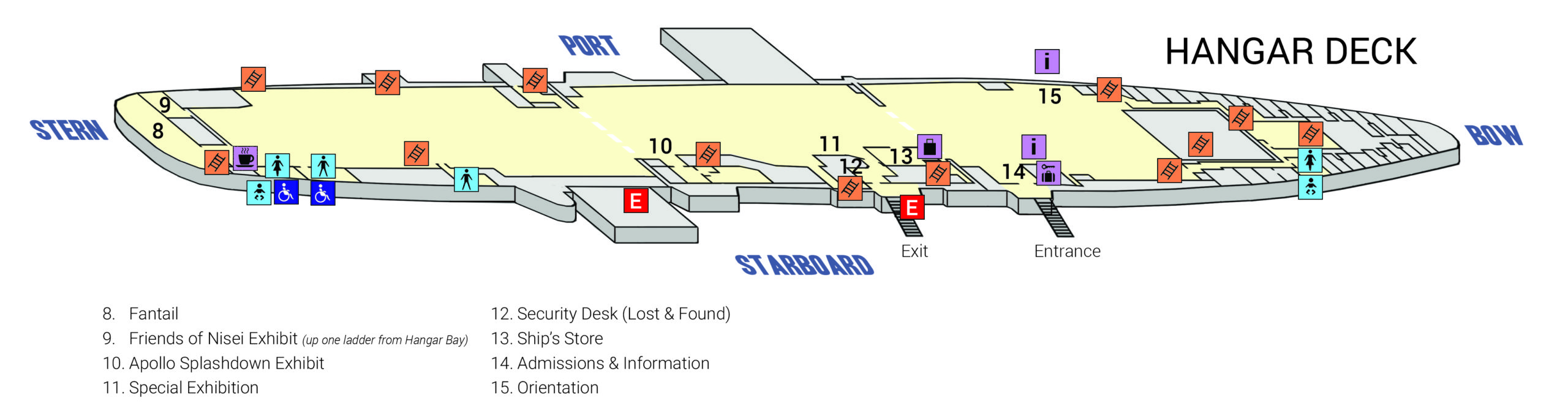

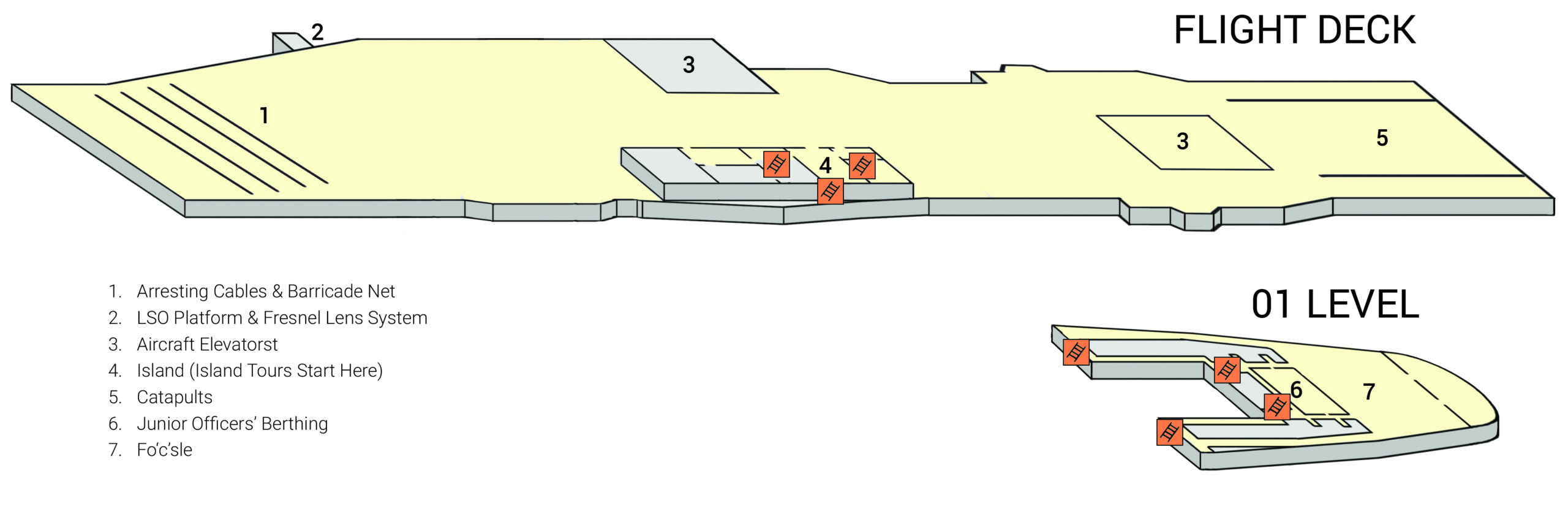

Navigating the Tour

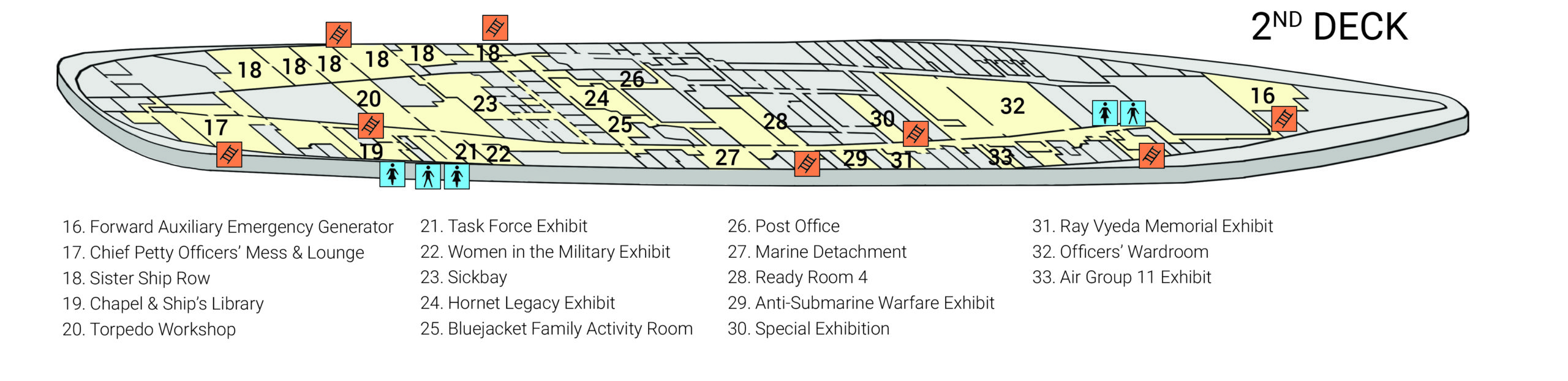

The tabs below have divided USS Hornet into her main touring spaces for you to search through. We may also refer to spaces by both their name and a number. This number will match to that spaces listing on our museum map, which you can find to the right if on desktop, or below if on your phone.

Hangar Deck

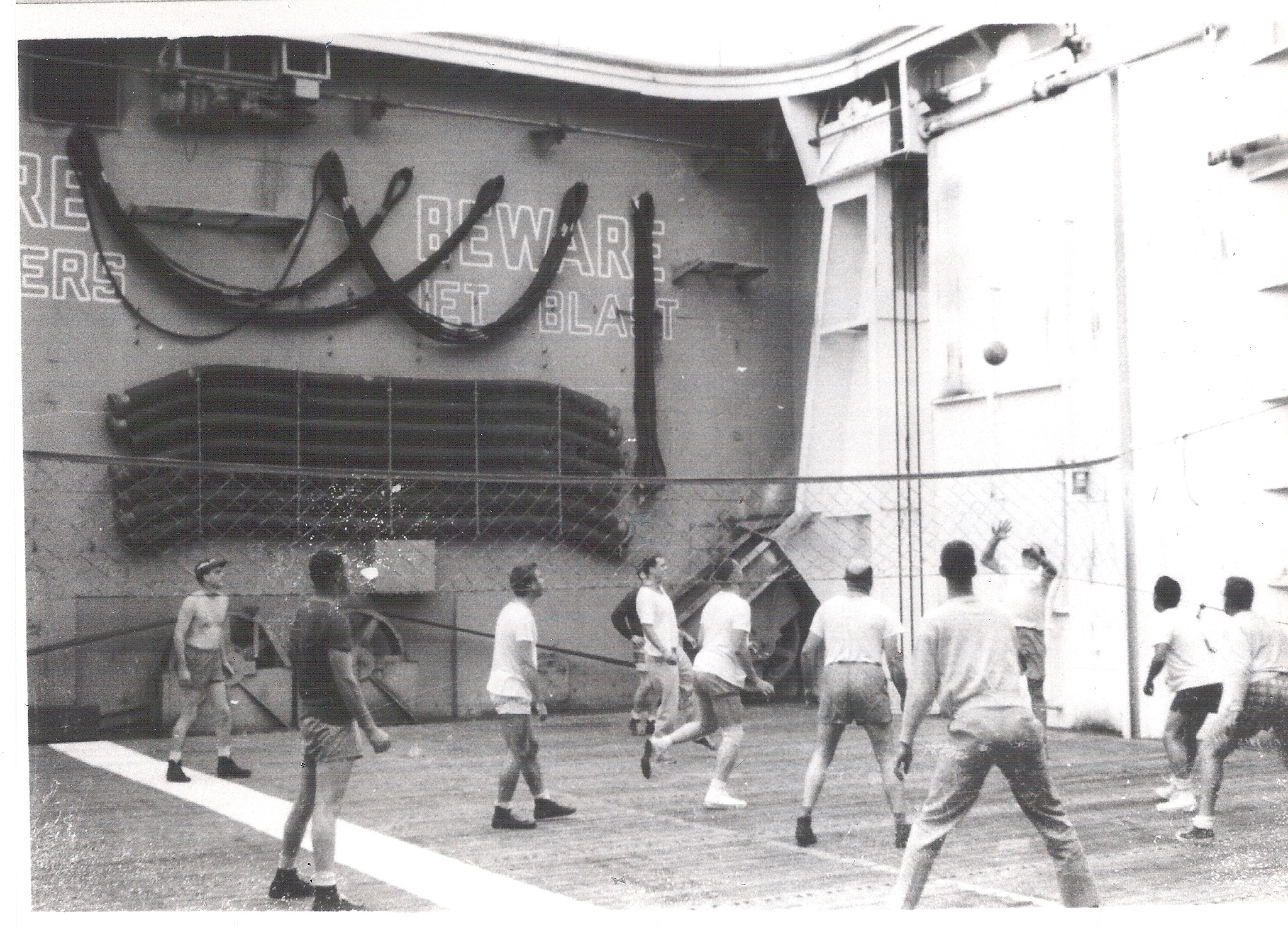

The Hangar Deck is the main deck of USS Hornet. Think of its main function as the parking garage and maintenance space for the ship’s aircraft. As the largest open space, it was also a popular place for ship-wide events for all of the ship’s sailors such as sport tournaments, movies and shows, church services, and other large assemblies.

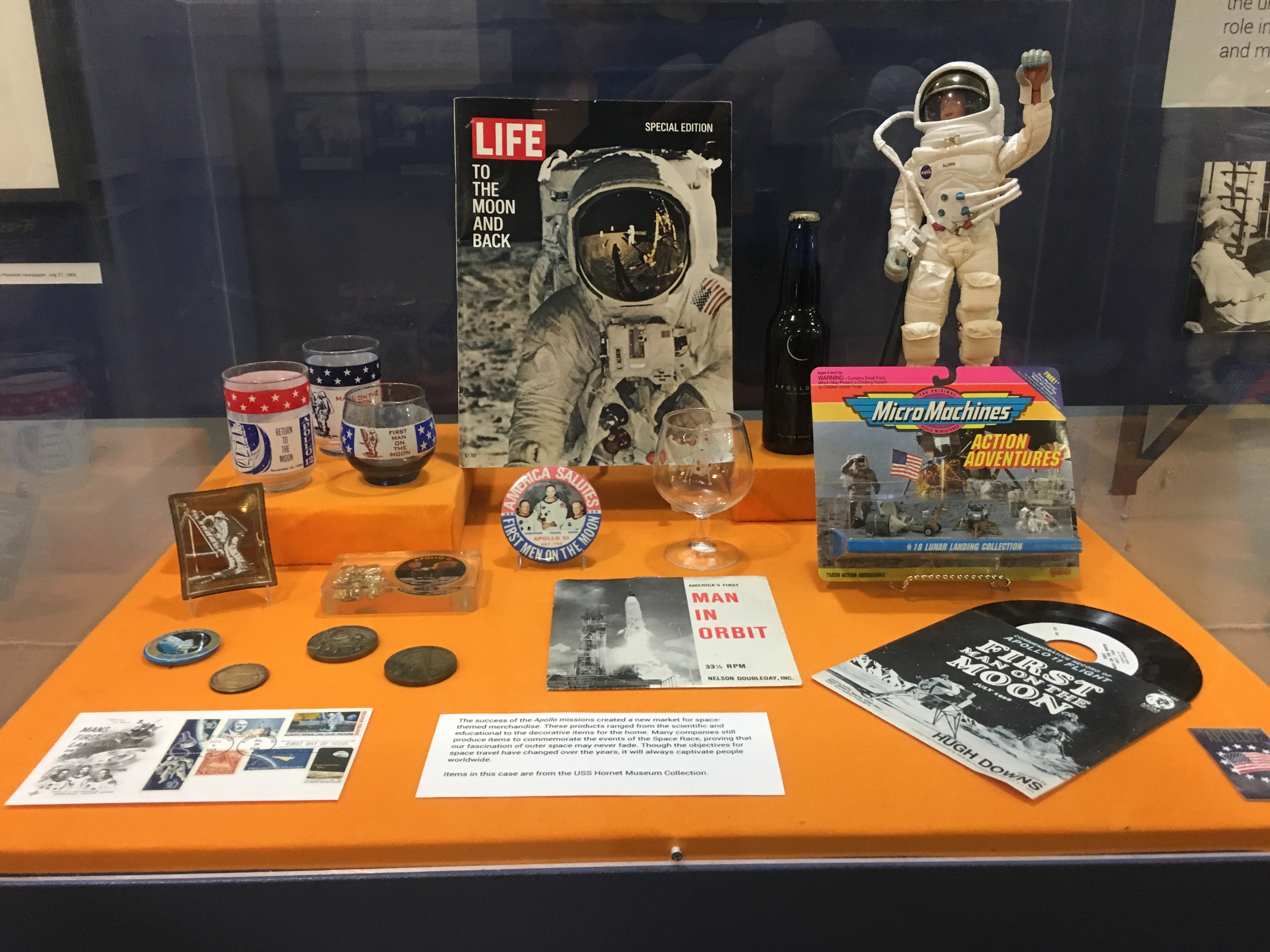

Today, it’s still one of the Museum’s main event and exhibition spaces! The Hangar Deck features most of the Museum’s historic aircraft, our Flight Simulator, Ship’s Store, and our exhibit on the Space Race and Apollo 11 and 12 programs! See the end for current and historic images of this deck!

8. Fantail

The Fantail is the rear or aft deck of a ship. Below the Fantail are the four propellers that propel the ship, each 15 ft (4.5 m) in diameter. It was one of the open areas on the ship and served as a crew lounge for men who were not standing watch, a classroom for learning skills such as rope tying, a platform for fishing, and a location for occasional ceremonies and services. When the ship was at sea a lookout was also posted here, alert for men overboard. The landing area of the Flight Deck is also directly overhead making this an exciting, if not potentially dangerous, place to stand while aircraft were landing.

9. Friends of the Nisei

This exhibit was installed by the Friends of the Nisei, a non-profit who worked with the Hornet Museum for this project. There are three main topics in these rooms: the 442nd Army Division, California’s Japanese-American internment camps, and the Military Intelligence Service.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, xenophobic tensions became magnified as the United States prepared for a potential Japanese assault of the West Coast. Japanese-Americans became referred to as “security risks”. On February 19, 1942 President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 directing the removal and internment of over 100,000 Americans of Japanese descent along the entire span of the Pacific Coast. Nearly 62% of Japanese-Americans interned in these camps were second generation Japanese-American United States Citizens, or Nisei. The conditions of the camps themselves were harsh, as barracks were lacking in privacy and indoor plumbing.

At the same time as these internment camps were in operation, the Army established the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an Asian American unit comprised primarily of volunteer Nisei Japanese-Americans. The 442nd served in both the European and Pacific Theaters during WWII but are best known for their service in Europe. They participated in one of the costliest campaigns on the German Gothic Line: the rescue of the “Lost Battalion,” serving with uncommon distinction while combating racial prejudices on the home front. The 442nd landed in Italy in 1944 before joining the invasion of southern France. They rescued the “Lost Battalion” at Biffontaine, suffering over 800 casualties to rescue 211 members of the 1st Battalion which had been surrounded by German forces. By April 1945, they pushed into Germany and were one of the first Allied troops to release prisoners from the Dachau concentration camp. The 442nd is said to have suffered a casualty rate of 314% (as in, the average soldier was injured more than three times), a statistic gained from the 9,486 Purple Hearts earned from some 3,000 in-theater personnel.

The Military Intelligence Service was a World War II U.S. military unit, primarily composed of Japanese-American Nisei who were trained as linguists. Graduates of the MIS language school were attached to other military units to provide translation and interrogation services. Near the end of the war with Japan, the curriculum shifted to focus more on Japanese civil affairs to assist with occupation and rebuilding after the war. The MIS was established in November 1941 and first operated at Crissy Field in San Francisco before later moving to Savage, Minnesota in 1942. MIS members attached to the joint Australian/American Allied Translator and Interpreter Service were instrumental in deciphering and translating the “Z Plan,” an important captured document that described Japanese plans for a counterattack in the central Pacific.

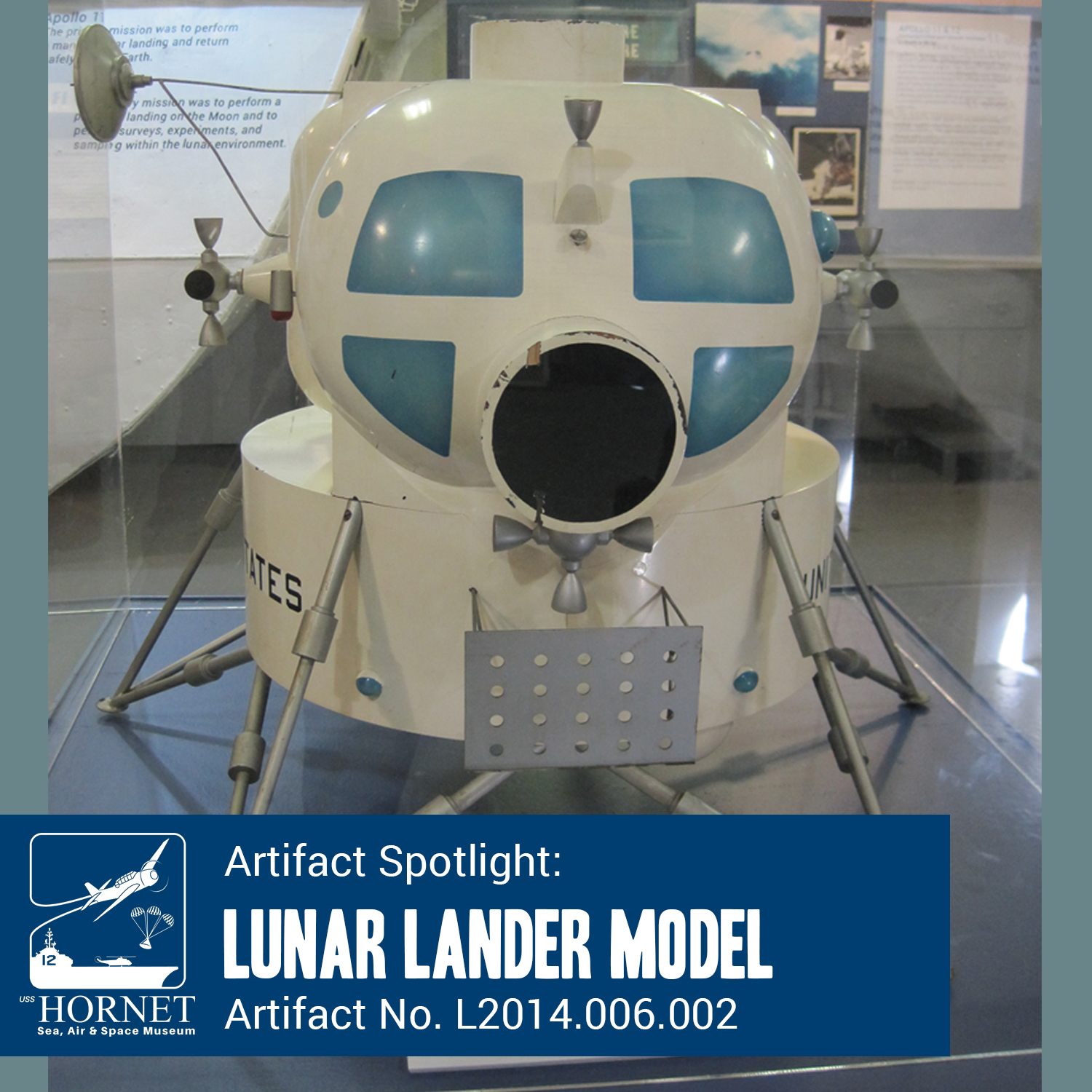

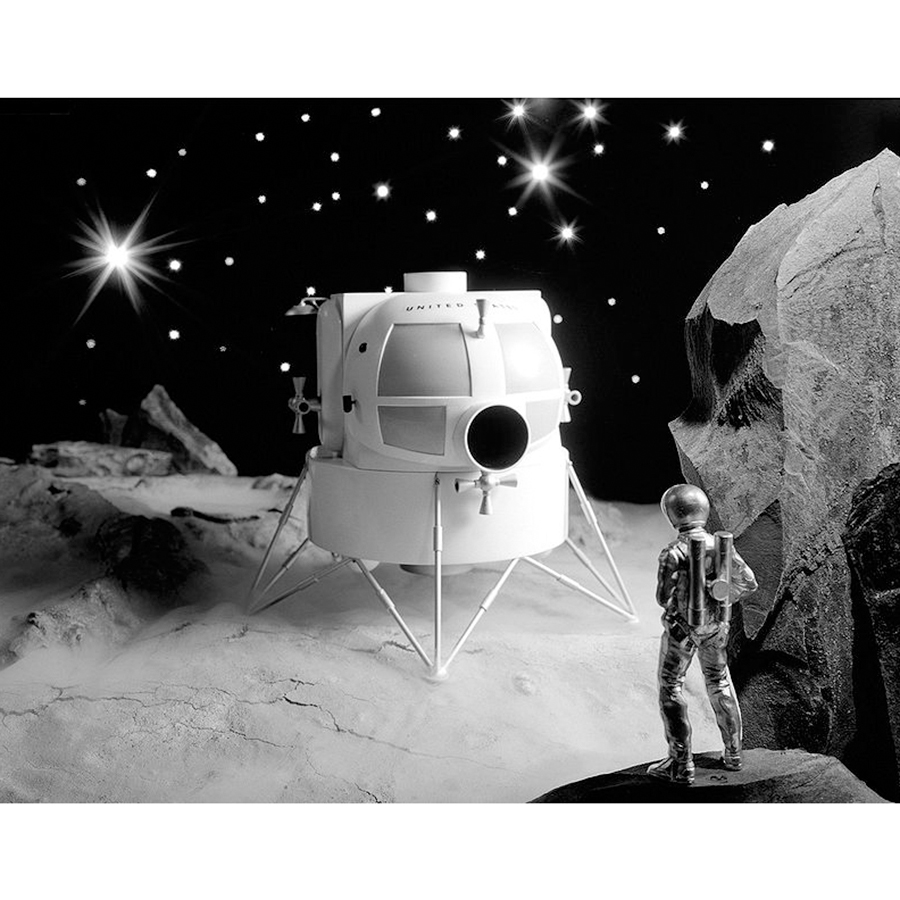

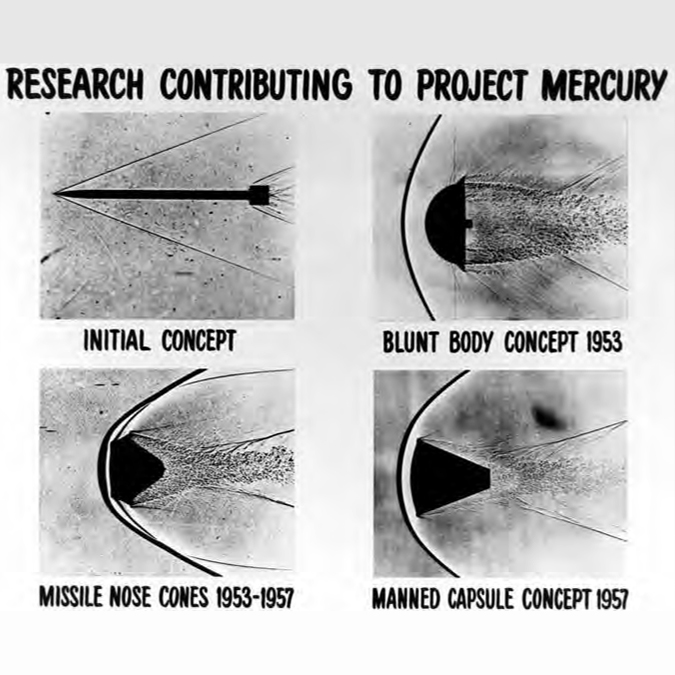

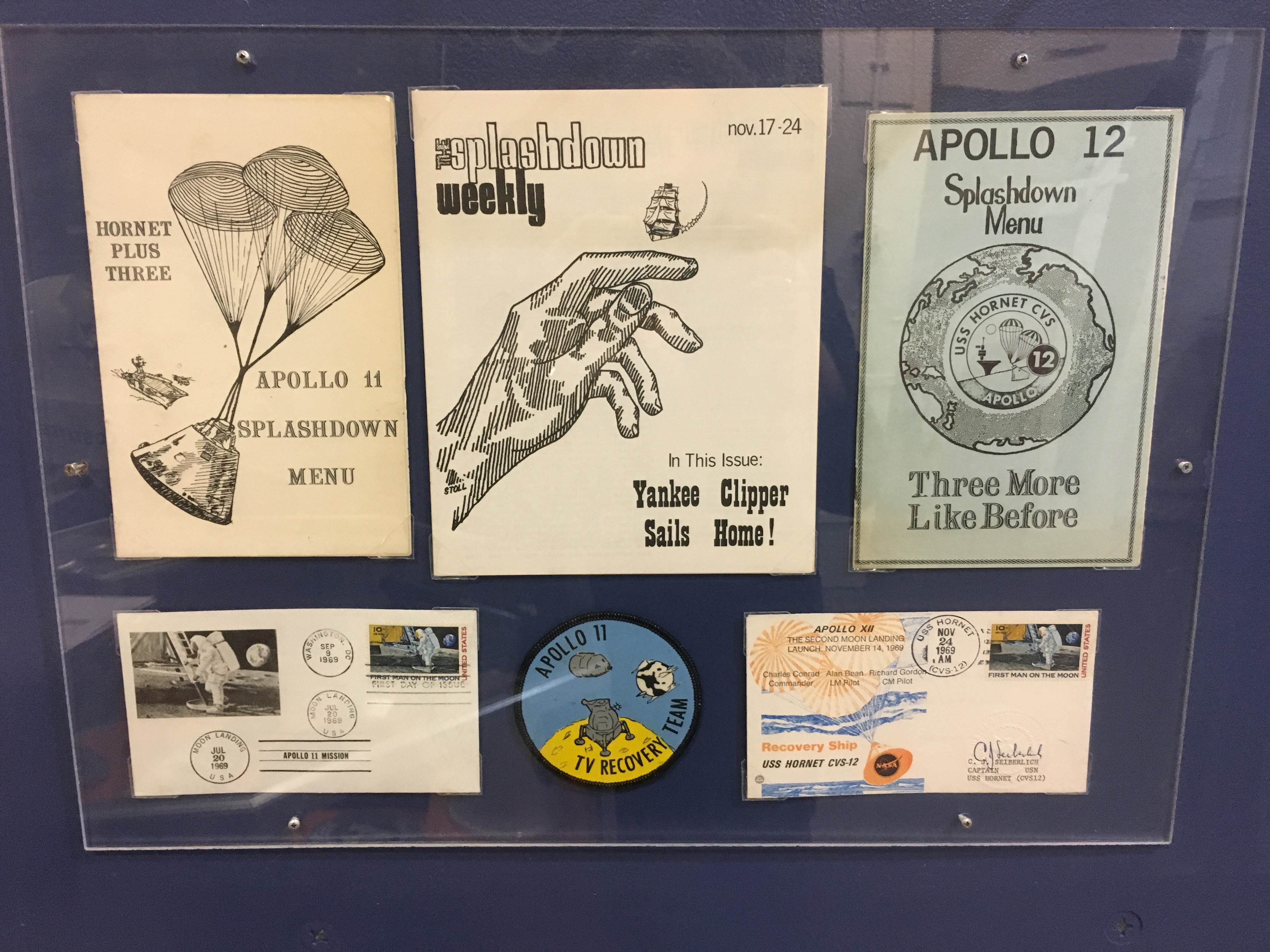

10. Apollo Splashdown

On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men on the Moon while Michael Collins orbited it in the CSM Columbia. On November 19, 1969, Apollo 12 astronauts Pete Conrad and Alan Bean landed the LM Intrepid in the Ocean of Storms and became the second Moon walkers, while Dick Gordon piloted the CSM Yankee Clipper.

On the return to Earth, both Apollo 11 and 12 were recovered in the South Pacific by USS Hornet. Specially trained Navy swimmers secured the capsule and airlifted its crew to the carrier. After safely retrieving the astronauts, Hornet hoisted the capsules aboard.

Recovering Apollo 11 and 12 finished Hornet’s extraordinary record of service. Apollo 11’s recovery was heightened by the presence of President Richard Nixon on board, a special event itself. In both missions, the astronauts were also placed into a Mobile Quarantine Unit (MQF) in case they had been contaminated out in space and remained aboard Hornet for a few days before the MQF was offloaded at Hawaii.

Flight Deck

An aircraft carrier’s Flight Deck is one of the busiest places on the ship. With an average of 300 men working among dozens of aircraft, flight decks are also the 4th most dangerous workplace in the world. Though the Museum has fencing around the edges of the deck now we installed those for guest safety. Add to that jet engine blasts or propellers, ordinance being loaded, and the challenges of landing with just about 200 feet of airstrip, and it was always an exciting place to be!

Today, guests can explore our Flight Deck risk free. The Flight Deck features a number of the Museum’s historic aircraft, and the Island superstructure that hosts the Captain’s Bridge and Combat Information Center. See the end of this section for current and historic images of this deck!

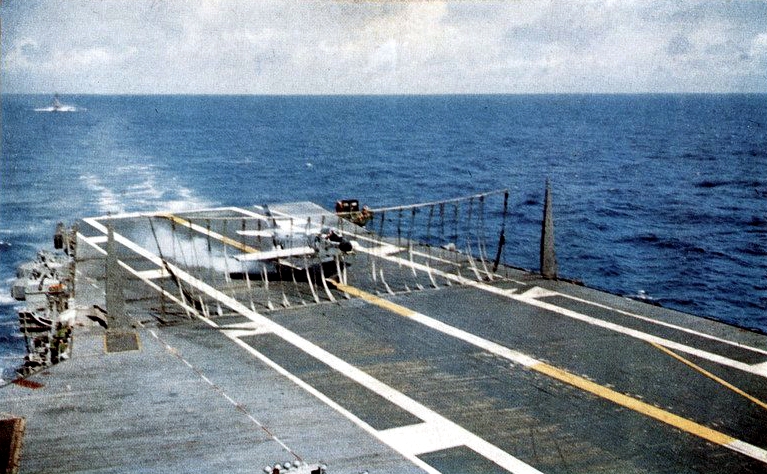

1 & 2. Landing Area

Landing an aircraft on the Flight Deck of an aircraft carrier at sea is a dangerous task reserved only for experienced pilots. All aircraft built for carrier use were equipped with “tailhooks,” hooks that lower from the back end of the aircraft designed to catch an arresting cable. Hornet’s Flight Deck had four arresting cables stretching across the landing area of her deck, each one able to trap and stop an aircraft in its tracks if the hook caught it.

A successful landing often came down to listening to the LSO, or Landing Signal Officer, who guided pilots into their landing from the small, framed platform on the port side of the Flight Deck off the landing area. In Hornet’s early days, propeller aircraft were slower, and the LSO could use brightly colored paddles, known as flag signals, to direct approaching aircraft. Jet aircraft were too fast for this manual system and so the digital Optical Landing System was installed about two-thirds of the way down the port side of the landing area. The Optical Landing System is a light device utilizing a fresnel lenses and reference lights in such a way that, if a pilot is correctly approaching, he will see the correct fresnel lens lit and know that he is level with the deck and can expect a successful landing. If the LSO anticipated an issue with a pilot’s landing, he would give them a wave off and have them fly around for another attempt. Some pilots would have a wave off multiple times before they were given permission to attempt a landing, particularly in rough weather conditions when the ship herself could be rolling in unpredictable ways.

If the approaching aircraft had a damaged tailhook or some other trouble that prevented use of the arresting cables, the Flight Deck crew could erect a Barricade Net that stretched across the deck between two stanchions. The pilot would fly into the net which would then wrap around the aircraft and drag it to a stop.

3. Aircraft Elevators

USS Hornet has three aircraft elevators. The first is forward centerline and connects Hangar Bay 1 to the Flight Deck near the catapults. The elevator is usually kept in the up position, flush with the Flight Deck. The other two were built on the port and starboard sides off the ship, with one in Hangar Bay 2 and the other in Hangar Bay 3. These elevators were used to quickly move aircraft between the Hangar Deck and Flight Deck, and each could move twenty tons, the weight of a fully fueled and loaded aircraft, between decks in under ten seconds.

Hornet’s elevators are suspended on twelve cables controlled by a hydraulic piston. The control valve can be operated electrically or manually. When operated electrically, the platform stops only at the Flight Deck or Hangar Deck. When operated manually with a hand wheel, the platform can be stopped at any position.

When they weren’t in use for aircraft movement, the elevators could be used as recreation spaces by the sailors. An elevator was a good size for setting up a volleyball or basketball game and was occasionally used as a diving board for an ocean swim.

4. Island Superstructure

Hornet’s “Island” is the superstructure rising from her Flight Deck. This part of the ship served as the command center and held the Captain’s Bridge, Pilot House, Navigation, Primary Flight Control, and, at its base, Combat Information Center.

The Captain’s Bridge and Pilot House are where the captain was expected to be when the ship was at sea. From his bridge, the Captain could see 25 miles (40.23 km) in all directions and would give orders to steer the ship back into the Pilot House where the Helmsman would control the ship’s wheel while the Lee Helmsman controlled the ship’s speed.

Navigation is on the same level as the Captain’s Bridge and Pilot House. During USS Hornet’s service, the Navigation crew had several ways to determine the ship’s position including piloting, celestial navigation, LORAN, and the Dead Reckoning Tracer. The LORAN (Long Range Navigation) system worked using a receiver on the ship that could sense low-frequency radio signals transmitted by fixed land-based beacons that then triangulated the ship’s positions based on the signals it received. The Dead Reckoning Tracer, meanwhile, was an analog computer that required the ship’s longitude and latitude but could then follow a changing position through speed and direction. Both methods have been outdated by modern GPS.

Primary Flight Control, or Pri-Fli, is the uppermost glass room on the Island and was where the Air Boss worked so that he could keep track of the aircraft and crew movement down on the Flight Deck below. His job was made slightly easier since the Flight Deck crew wore color-coded uniforms which indicated their duties so he could be sure that they were all where they were supposed to be.

Finally, Combat Information Center (CIC) is at the base of the Island and was where Hornet gathered information about the ships and aircraft around her. Equipment in CIC was used to track and identify movement under the water, along the surface of the water, and up in the air. Submarines, ships, and aircraft would be identified as friend or foe based on the radio signals they emitted and other identifiers and their movements would be tracked on large plotting maps.

5. Aircraft Catapults

An aircraft carrier’s Flight Deck is a dangerous place to work and usually had 300 men working among moving aircraft and machinery—and with none of the fencing you see around the deck today. The ship’s two catapults made it possible to launch aircraft with a limited runway. They are H-8 hydraulic catapults powered with compressed air and could take the aircraft from 0 to 120 mph in about 3 seconds. The machinery to power the catapults is over six decks below with more than 1000 ft of cable connecting the machinery to the Flight Deck track. (This area is sometimes available for docent-led tours.)

Aircraft were launched basically being pulled off the deck at high speed. They were attached to the catapult with a “bridle” affixed under its wings that then wrapped around a shuttle on the catapult. They were also then attached to the Flight Deck by a “holdback bar.” The holdback bar allowed the aircraft to bring their engines to full power. When the pilot was ready, he would signal to the deck crew and the catapult was launched. The combined power of the catapult stroke and the aircraft’s engines would snap the holdback bar at its thinnest point and the aircraft would go flying forward and off the deck.

6. Junior Officers’ Berthing

An aircraft carrier is, at its heart, an airport that can cross oceans. Hornet would typically deploy with a Carrier Air Group made of 3-6 squadrons. During WWII, Air Groups would usually include a Fighter Squadron, Bombing Squadron, Scouting Squadron, and Torpedo Squadron and consisted of over 100 aircraft. Later, different squadron types, such as Anti-Submarine and Helicopter Squadrons, would be added to the mix. Each squadron had 12-24 aircraft and pilots.

All pilots are officers, so they generally stayed in the forward section of the ship along with the officers of the ship’s company. Junior Officers’ Berthing (or “J.O.B.”) was the “worst” accommodations an officer could expect aboard USS Hornet, still far better than most enlisted compartments, and was home to some of the ship’s newest pilots.

In this room, you can see safes where the pilots would store their sidearms when they weren’t flying—aboard the ship, only Marines could carry firearms. You can also see a table. J.O.B. was typically kept in nighttime conditions to accommodate pilots sleeping at all hours due to varied missions. There was a curtained area where the table was that was lit with white lights so the men could do quiet activities within their compartment.

Lastly, you can see a large vent by the table which is an air conditioning unit. This was installed after WWII. During the 1940s, the only areas that were air conditioned were Sickbay and spaces with sensitive machinery.

7. Foc’s’le

The name “Foc’s’le” is shorthand from “Forecastle” and refers to the castle-like structure which rose above the front of old wooden sailing ships. Its primary function aboard Hornet is to hold her two anchors.

Each chain is raised with the aid of a winch called a wildcat, which are the brass domes that the chains wrap around. Each wildcat sits atop an anchor windlass, which uses a hydraulic motor to raise the anchor. When the anchor is fully raised, the chain is secured to the deck by clamps called pelican hooks, so-called because they look like large bird beaks.

When it was time to drop anchor, sailors would remove the safety pin in each pelican hook with a sledgehammer, use a very large lever to lift the chain, and then slide the pelican hook and its chain out of the way so the anchor chain could run freely as it was released. The sailors would run to the back of the foc’s’le before the chain released so as to be out of the way as it whipped across the deck in a free fall. A brake on the wildcats allowed sailors to stop the chains at the desired depth.

achinery.

Second Deck

A ship’s second deck was a mix of living and working spaces but has the largest number of individual spaces available to our guests for self-touring! See the end of this second for images of some of the spaces!

16. Forward Emergency Generator

This is the Forward Emergency Diesel Generator. A second, identical generator is in the aft portion of the ship and, together, both could supply all critical electrical power needs in case the main generator in the Engine Room failed or shut down. Crewmen would monitor the generator when it was not in use and tested it periodically to make sure it was in working order. The podiums and desk held logbooks and records of this testing, that was maintained by the crew who slept in the racks (bunks) in this space.

Each generator had an engine that started using 250 psi compressed air and was rated at 1,416 HP and generated 1,000 kilowatts (1,600 amps) at 440 volts 3 phase.

17. Chief Petty Officers’ Mess & Lounge

The rank Chief Petty Officer (CPO) is the seventh enlisted rate (with the paygrade E-7) in the U.S. Navy, just above petty officer first class and below senior chief petty officer. Advancement into the chief petty officer grades is the most significant promotion within the enlisted naval grades. At the grade of chief petty officer, the Sailor takes on more administrative duties. In the U.S. Navy, their uniform alters to reflect this change of duty, becoming identical to that of an officer’s uniform except with different insignia.

Personnel in the three chief petty officer rates (E-7 through E-9) also had conspicuous privileges such as separate dining and living areas. Their mess was off-limits to anyone who not a chief, including the captain himself, except by specific invitation.

18. Sister Ship Row

The portside of the 2nd Deck is dedicated to Hornet’s 23 sister ships, so called because all 24

Essex-class aircraft carriers were built from the same basic blueprint. Out of all 24 sister ships, only four remain today: USS Hornet, USS Intrepid, USS Lexington, and USS Yorktown, all of which are museums you can visit. Happily, no Essex-class ships were sunk during WWII, though some were severely damaged. The remainder of the ships were eventually decommissioned and then most were scrapped, though, notably, USS Oriskany was intentionally sunk to become an artificial reef off the Florida coastline.

Every ship had a unique story, and every one of them added to the greater narrative of what it meant to be an Essex-class aircraft carrier.

In these six rooms dedicated to Hornet’s sister ships, you can see the following ships and their stories:

- Room 1: USS Lake Champlain, USS Tarawa, USS Princeton, and USS Antietam

- Room 2: USS Bennington, USS Leyte, and USS Kearsarge

- Room 3: USS Wasp, USS Yorktown, USS Bon Homme Richard, and USS Valley Forge

- Room 4: USS Shangri-La, USS Ticonderoga, and USS Lexington

- Room 5: USS Essex, USS Oriskany, USS Hancock, and USS Boxer

- Room 6: USS Franklin, USS Philippine Sea, USS Randolph, and USS Bunker Hill

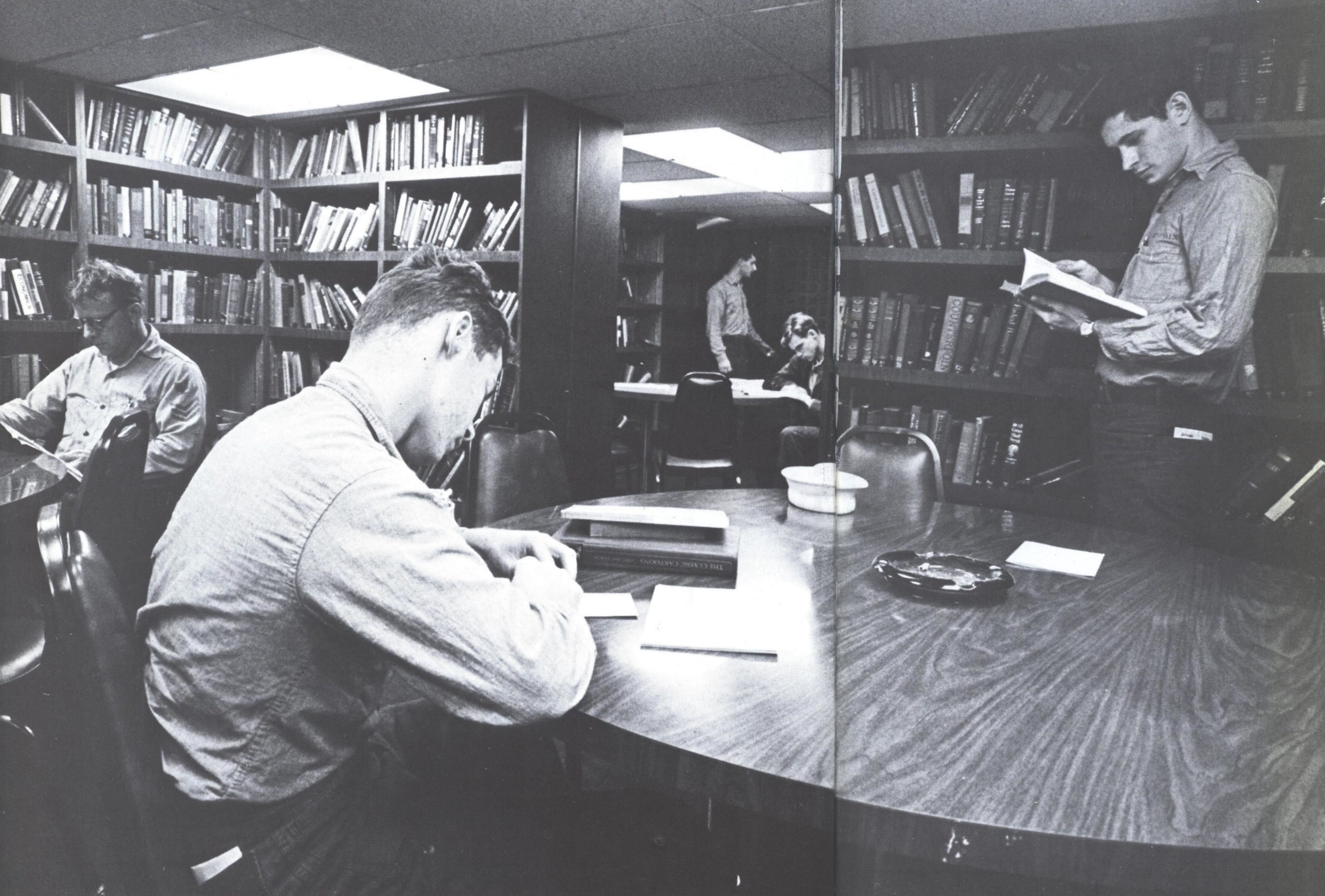

19. Chapel & Library

As with most of the U.S. Navy’s larger ships, USS Hornet’s crew included one or two Chaplains. Navy chaplains have a specific faith group they follow and represent, but the chaplains on board also facilitated religious support for sailors of all faiths while they were aboard. If any faith group didn’t have a chaplain aboard who represented them, a sailor of that faith volunteered as a certified lay leader.

The role of the chaplain on board was talking to sailors and offering counseling. A formal Catholic confessional was available aboard USS Hornet (marked out now by curtains) but sailors of any or no faith and regardless of rank could make use of the chaplain’s counseling services by visiting them in their offices.

This compartment also contained the ship’s library which functioned similarly to a public library. Bookshelves were lined with new and used books that sailors could read in the space or take with them back to their rooms. Additional bookshelves would have held a collection of the Navy’s professional reading list.

20. Torpedo Workshop

This is the Torpedo Workshop. USS Hornet could not launch torpedoes like a submarine can, but she did, at times, carry bomber aircraft that could hold one or more torpedoes and so needed to keep torpedoes on board during those times.

This workshop is where sailors would assemble the torpedoes. For safety, they were kept in two parts down below in storage and so had to be put together before being sent up to the Hangar or Flight Deck for loading onto aircraft. If the sailors working here had enough forewarning, they could start to stockpile assembled torpedoes by storing them in the berthing space adjacent to the workshop by dropping the racks off their chains. This is the reason the I-beams on the ceiling go out into that compartment. Otherwise, there is an elevator that takes the torpedoes up to the Hangar Deck to be loaded onto aircraft.

In Torpedo berthing, the bulkhead (wall) opposite the torpedo workshop also contains one of the locations from where the ship can be steered if she were damaged in battle. It was made to be used only if the Island and Sec Conn in the Foc’s’le were not operational, which would mean that the ship would be in dire straits. The steering console includes a Rudder Angle Indicator, a compass, a toggle switch to direct the rudder, and sound-powered headphones to listen to directions on how to steer the ship out of danger.

21. Task Force Exhibit

A task force is a group of ships assembled for a specific assignment, bringing together different divisions and squadrons without the need for a formal fleet reorganization. Task forces work well for the changing needs of war, and, by the end of World War II, about 100 task forces had been created by the U.S. Navy. Task forces could comprise many different types of ships including aircraft carriers, submarines, destroyers, light cruisers, and more. The task force would also be given a designated number—even numbers for the Atlantic and odd numbers to the Pacific—and could also be broken down into various subgroups: battle groups, task units, and task elements.

Whenever a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier is called out to sea it is part of a battle group. A carrier battle group is a battle group specifically centered around an aircraft carrier with escorts surrounding her. These other ships can include destroyers, smaller escort carriers, and more.

Types of ships that could be found in a Navy task force include:

- Destroyer (DD): A fast moving, maneuverable, long-endurance warship

- Light Cruiser (CL): A small to medium sized warship

- Submarine (SS or SSN): A watercraft capable of independent operation

- Escort Carrier (CVE): A flat top carrier is half the length and third the displacement of the larger fleet carriers, slower and less well armed and armored

- Amphibious warfare (LST): A narrow, amphibious personnel carrier

- Aircraft carriers (CV, CVA, CVS): A flat top warship which serves as a seagoing airbase

- Auxiliary Ship (AB, AC, T-ACS, AD, YDG, ADG, AE): A naval ship designed to operate in several roles supporting combatant ships including replenishment, transport, repair, harbor and research

- Battleships (BB): A large armored warship with large caliber guns capable of bombarding enemies on land and sea

- Cruisers (CL or CA): Originally built for scouting for the battle fleet, cruisers have replaced battleships as the primary surface combatant

- Destroyer Escorts (DE or DEE): Designed for endurance and escort, they were mass-produced for WWII as a less expensive anti-submarine warfare alternative

- Gunboats (PG): A naval watercraft designed for bombarding coastal targets.

22. Women in the Military

Women served among the United States military as early as the American Revolution as battlefield nurses and water bearers. Women’s main roles on the war front were to act as civilian nurses until 1901 when the Army Nurse Corps was established, followed next in 1908 by the Navy Nurse Corps. While they never held actual rank, Army and Navy nurses were accorded privileges like those of officers.

During the last two years of World War I, women were allowed to join the military. 33,000 women served as nurses and support staff officially in the military. 11,275 of those women served in the Navy as Yeomen in mostly clerical roles, though they also served as translators, draftsmen, fingerprint-experts, camouflage designers, and recruiting agents.

In WWII, more than 400,000 women served at home and abroad as mechanics, ambulance drivers, pilots, administrators, nurses, and on other non-combat roles, but it wasn’t until 1948, after the war ended, that women were granted permanent status in the military and entitled to veterans’ benefits.

It also wasn’t until 1976, that the first females were admitted to the service academies such as West Point and the Air Force Academy to be trained in military science. In 1991, Congress finally authorized women to fly in combat missions and in 1993, Congress authorized women to serve on combat ships. As recent as March 2016, Defense Secretary Ash Carter approved plans to open all combat jobs to women to fully integrate female combat soldiers.

23. Sickbay

USS Hornet had a fully functional hospital, called Sickbay, to take care of an average 3,500 men. Staff included 4 doctors and about 24 corpsmen. Sickbay was equipped with a general examination room, x-ray room, bacteriological lab, vision and sound testing rooms, a laboratory, pharmacy, offices, and two surgical rooms.

It also hosts a Ward that can sleep some 50 sailors who were too ill or injured to return to their regularly assigned bunks. Inside the Ward was the Quiet Room, a smaller room for up to 4 people that had its own head, which was available for those who might be particularly ill or contagious or otherwise needing more privacy.

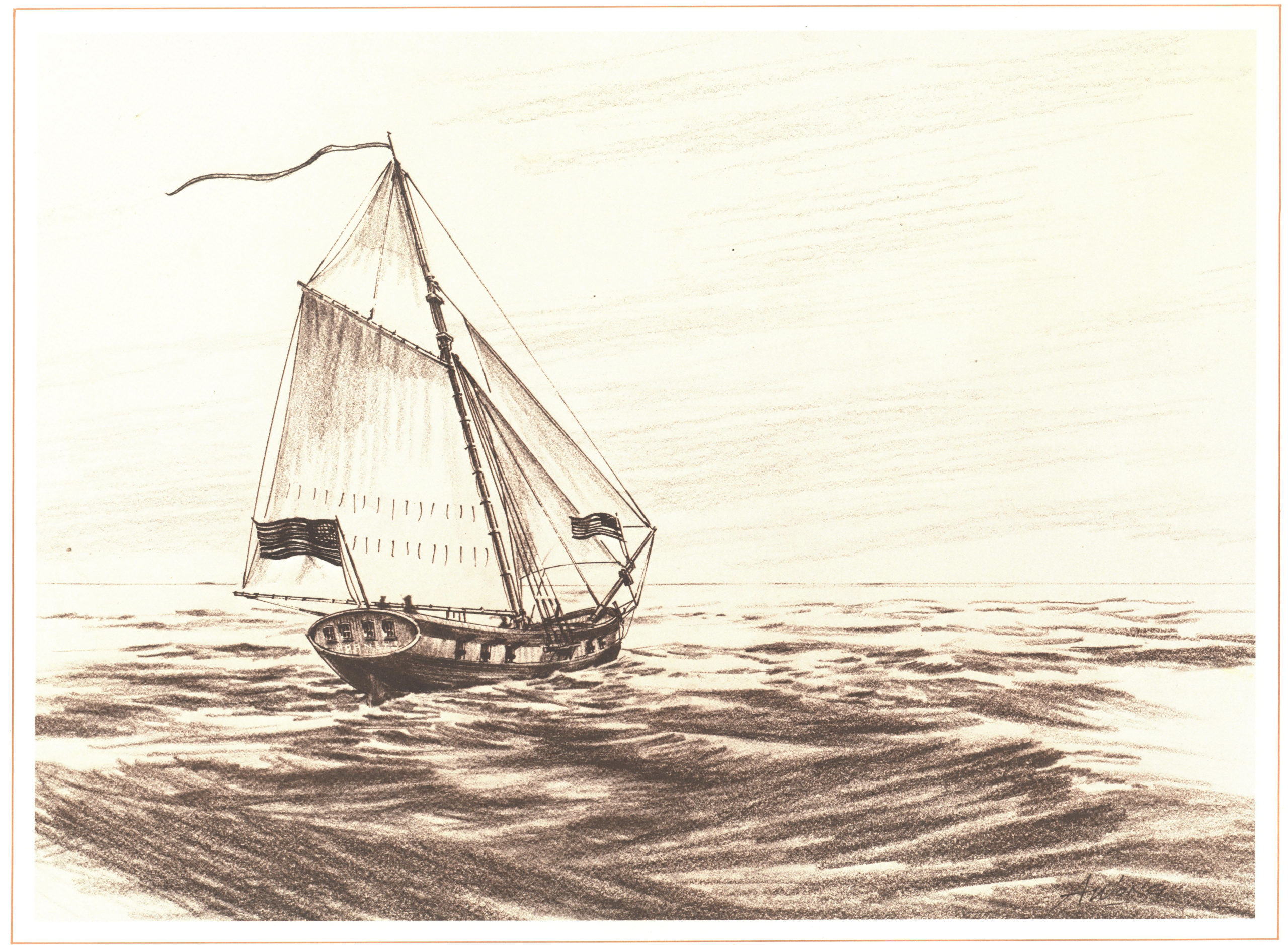

24. Hornet Legacy Room

The name Hornet dates back to the earliest days of the United States and has been carried through eight ships, the last being this aircraft carrier. The first USS Hornet was one of the first two ships commandeered by the Continental Navy to fight against the British during the Revolutionary War. The other was USS Wasp and, together, they were used to “sting the British fleet.”

Since then, Hornets have fought Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean, the British during the War of 1812, the Confederates during the Civil War, and Spain during the Spanish-American War. The seventh Hornet was the aircraft carrier CV-8, commissioned in 1941, which became famous for being the ship that carried the Doolittle Raiders across the Pacific, the first U.S. air raid to strike the Japanese home islands after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The eighth Hornet, the one on which you stand, performed so admirably during her service that the name Hornet was carried on to the F/A-18 Super Hornet jet even while the ship still floats.

26. Post Office

Mail has long sustained the vital connections between military service members and their family and friends, as well as maintained connections to their community.

The Army Post Office was developed in WWI and was put to the test in WWII when they processed mail for millions of American men and women serving in the armed forces. The Navy’s Fleet Record Office alone maintained thousands of cards for tracking and updating address changes for sailors in the Navy.

Sending and delivering mail is made possible by exchanging mail at port of call, or at sea through “underway replenishment (UNREP).” UNREP is the process when two ships moving parallel to each other exchange information, mail, or supplies from one to another while at sea.

Mail is very important to sailors deployed at sea. Mail from home delivers emotions, connections, love, and a touch of family. Reading and writing letters are an easy escape from the harrowing experience of war. It brings sailors a reminder of people and places that they love and provides moments of normalcy and reassurance.

27. Marine Detachment

A Marine Detachment was a separate division on board a U.S. Navy ship. Aboard USS Hornet, the Marine Detachment consisted of about two officers and 46-55 Marines. They were the only ones aboard the ship allowed to carry firearms and, during WWII, preferred the M-1 rifle. The Marine Detachment performed several functions, including:

- They acted as part of the ship’s landing force if needed.

- They provided the captain with an orderly, a guard position that dates to older sailing days where mutiny was more likely. They also provided brig sentries and special weapons (nuclear) sentries.

- The provided gun crews to man several of the ship’s anti-aircraft guns.

- After WWII, they crewed helicopters aboard USS Hornet for search and rescue, plane guard, and general transport duties.

But times have changed. Ships’ guns were replaced with guided missiles and computer-controlled weapons systems for defense, and the role of Marine Detachments diminished. In January 1998, Marine Corps Headquarters announced that all Marine ships’ detachments were to be disestablished. Marines are still aboard U.S. Navy amphibious ships, however, to continue serving as the U.S. Navy’s landing force.

28. Ready Room 4

This room, Ready Room #4, was used by pilots aboard USS Hornet before, during, and after missions and, outside of combat, as a training room. When a carrier air wing was assigned to a carrier, each of its squadrons were given their own Ready Room. To the pilots, their Ready Room was like a clubroom as well as a place to store their flying gear which would have included parachutes, harnesses, and helmets.

Aircraft carriers like USS Hornet were built to be floating airports so pilots were an essential part of the ship. To become a carrier pilot, men and women must pass strict requirements and go through intense training programs. Between January 1941 and August 1945, nearly 325,000 young men entered the cadet training program to fly in World War II. About 191,000 of them, or 59%, graduated. Most of the remaining dropped out while a few perished in accidents during training.

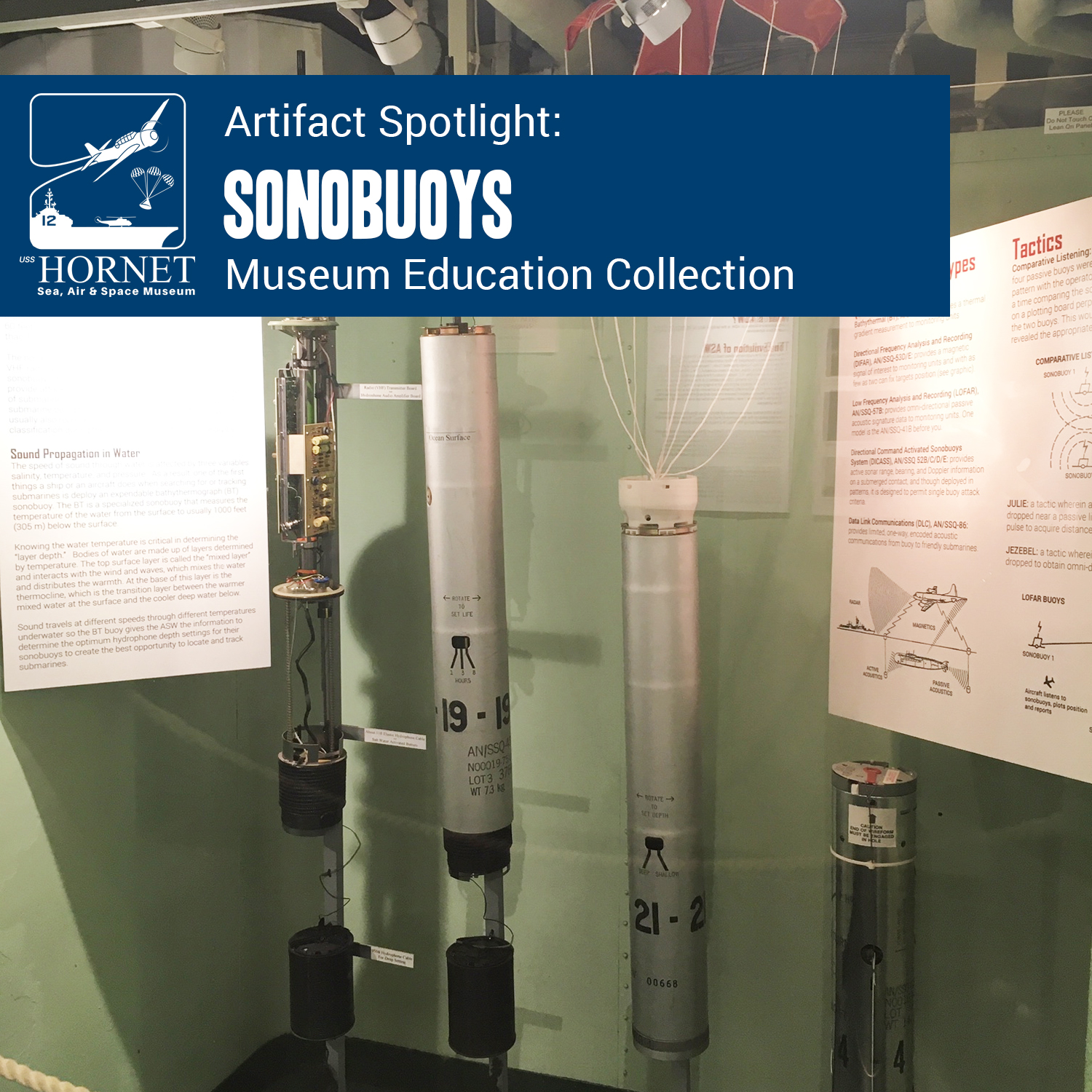

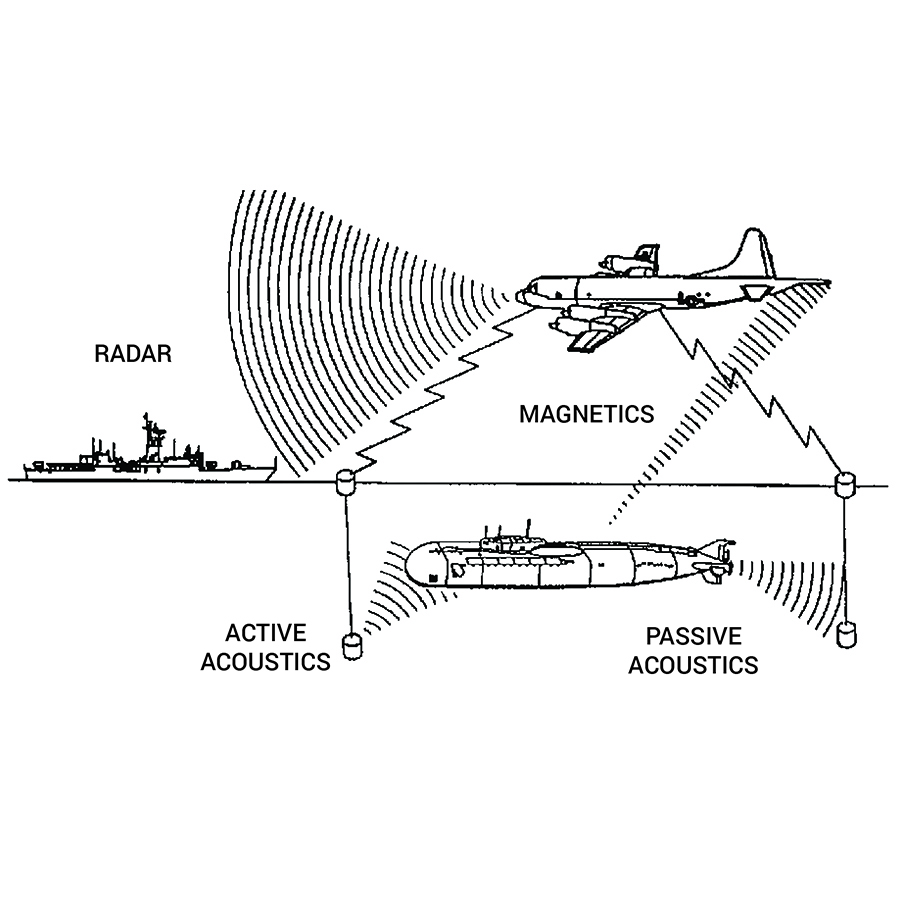

29. Anti-Submarine Warfare Exhibit

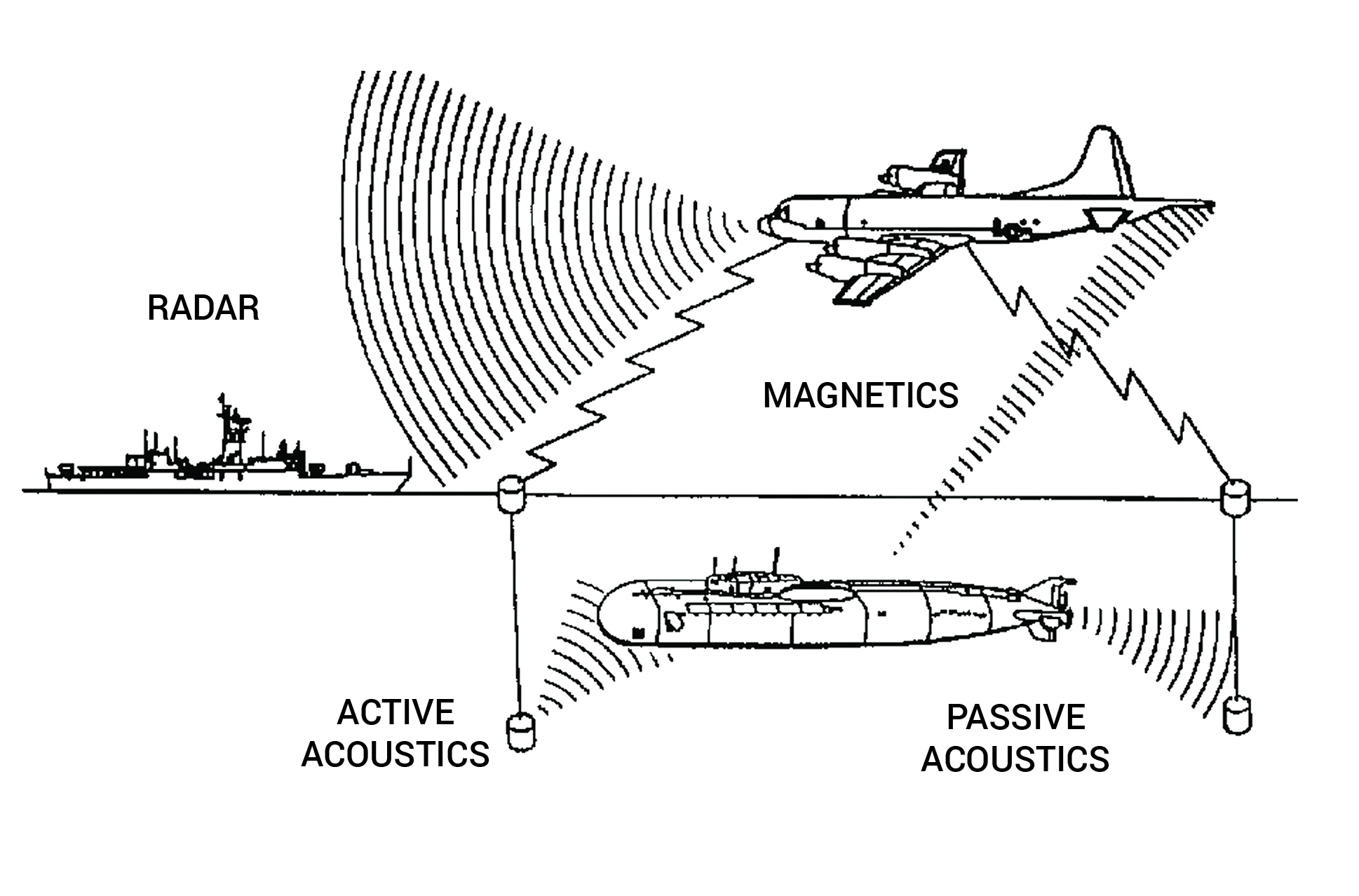

Anti-Submarine Warfare, or ASW, is the tactic of denying the enemy the effective use of their submarines.

The concept of the submarine dates back to the late 16th century. The Continental Navy developed the first submarine for military use, David Bushnell’s one-man, human-propelled Turtle during the Revolutionary War. By World War I, the submarine was a threat that needed to be addressed. Early ASW tactics included draping nets across channels to snare subs and developing depth charges.

In WWII, German submarines in the Atlantic caused heavy losses of merchant fleets transporting war materials to Europe and Africa. The U.S. Navy developed new combat techniques with aircraft such as Grumman Avenger torpedo bombers and Wildcat fighter aircraft. Their aircraft carriers and the ships that protected them became known as Hunter Killer Groups (HUK) and helped stem heavy shipping losses.

After WWII, nuclear-powered submarines were built that could launch ballistic missiles, and ASW tactics quickly evolved during the post-WWII and through the Korean War eras, becoming essential to the Cold War between the U.S. and Soviet Union. New inventions such as sonobuoys, SONAR systems, and Anti-Submarine rockets helped carriers and other ships find, identify, and destroy enemy submarines.

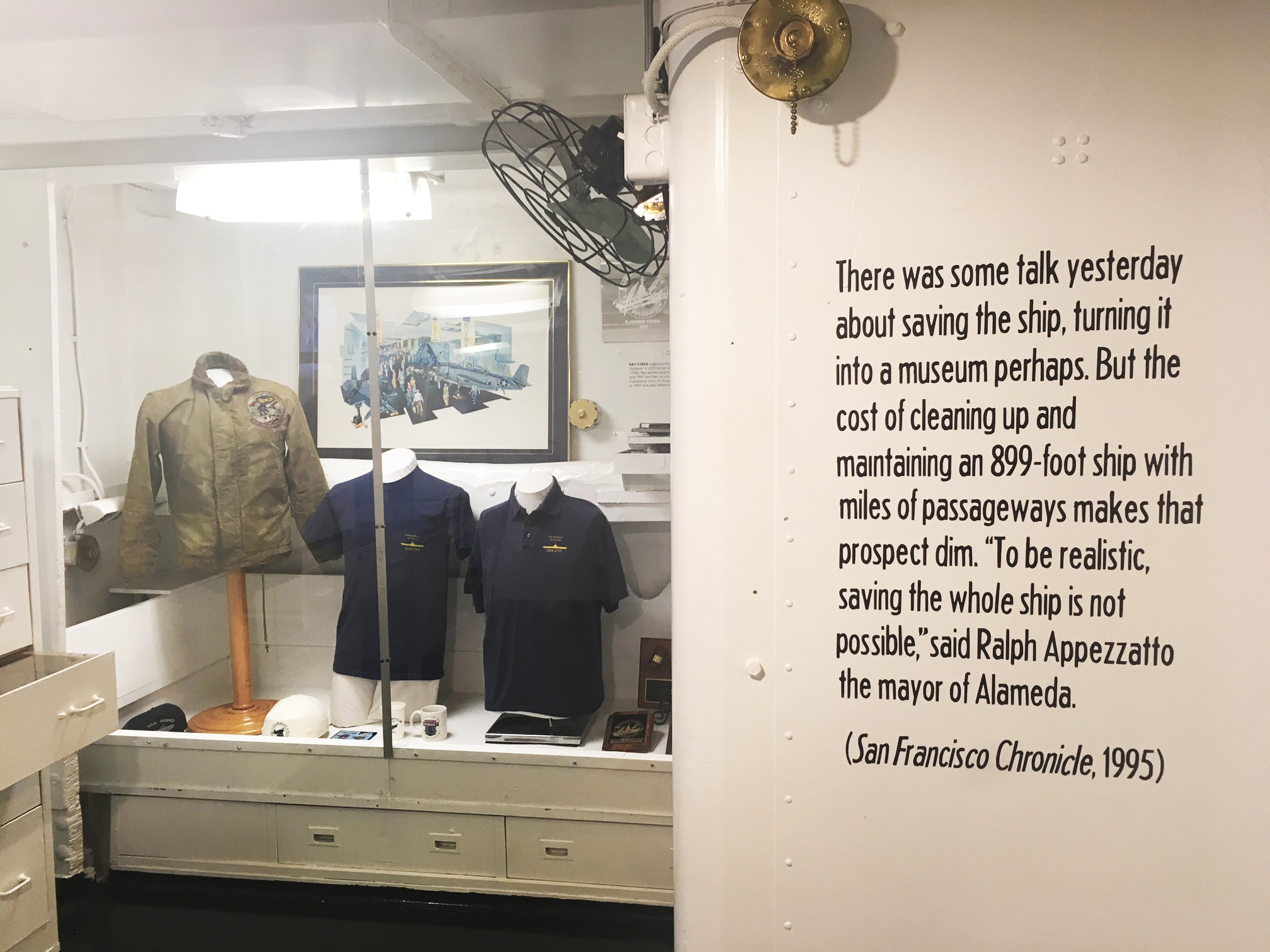

31. Ray Vyeda Memorial Exhibit — Mothballs to Museum

On January 15, 1970, very shortly after she recovered the astronauts of Apollo 11 and 12, the Navy announced that USS Hornet (CVS-12) would be deactivated and placed into mothballs.

In March 1970, USS Hornet began deactivation at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard in California. One month later she made her way north to Bremerton, Washington to continue deactivation and preservation work. In Bremerton, her boilers and piping systems were drained, machinery and equipment coated in preservation compounds, and her hull was corrosion-proofed. On June 26, 1970 Hornet was formally decommissioned.

Though the plan was to potentially reactivate Hornet at some point in time, detailed inspections in 1981 and 1987 found that her systems were obsolete and the living conditions were outdated for contemporary standards. In 1989, her name was officially stricken from the Naval Registry.

From 1970, Hornet sat in the mothball fleet, slowly being lost to history, until a group called The USS Hornet Historical Museum Association Inc. was formed to save the ship and turn the carrier into a museum. Thanks to the great efforts that these dedicated volunteers started, Hornet was rescued from being scrapped.

32. Officers’ Wardroom

Officers and enlisted sailors might have all been aboard Hornet together, but their experiences were very different. The forward third section of the ship is mostly all dedicated to officers, who made up only about 10% of the crew, or around 300-350 men. They had staterooms similar to college dorm rooms that they shared with a few roommates and usually ate in the Wardroom.

The Wardroom was the main mess area for the officers of the ship. Unlike the cafeteria-style chow line that the enlisted crew had down on the 3rd Deck, food here was served as in a restaurant, with stewards acting as cooks, waiters, and bussers. Also unlike the enlisted men, officers had to pay for their meals whereas food from the enlisted mess was given for free. The tables in the Wardroom were set with tablecloths, silverware, and china and officers were expected to dress in the uniform of the day.

Food for the Wardroom was prepared one deck below in the Wardroom Galley and then brought up to this Wardroom Pantry via dumbwaiter, where it was then plated and served. Some items, like eggs made to order, were cooked here for quick service. The hatch across from the Pantry leads down to both the Wardroom Galley and the Flight Suit Mess, a space where officers could eat without having to put on their full uniform and which was named for the pilots who might be suited up for a mission. The Flight Suit Mess, Wardroom Galley, and Wardroom Pantry were operational 24-hours-a-day to accommodate erratic mission schedules, though officers would have access to more limited menu options off-hours from breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

33. Air Group 11 Exhibit

An aircraft carrier is, at its heart, a floating airport dedicated to serving the air groups that fly off her. This included Air Group 11, which flew off USS Hornet from 1944-1945 in the Pacific Theater during WWII.

Carrier Air Group Eleven (CVG-11) was established on October 10, 1942 at Naval Air Station San Diego and included Bombing Squadron Eleven (VB-11), Fighting Squadron Eleven (VF-11), Scouting Squadron Eleven (VS-11) and Torpedo Squadron Eleven (VT-11). CVG-11 arrived when the Pacific combat zone had only one operational aircraft carrier, so the air group was land-based at Guadalcanal. Notably, on June 16, twenty-eight pilots of VF-11 engaged an estimated 120 Japanese planes and shot down 31. In August of 1943, they were sent back to NAS Alameda where they were reassigned to USS Hornet.

While on board USS Hornet, CVG-11 attacked targets on Okinawa, Formosa, the Philippines, French Indo China, and Hong Kong. The air group faced the threat of kamikaze attacks, foul weather, and anti-aircraft fire over intended targets but took personal pride that no VB-11 or VT-11 aircraft were lost to enemy fighter planes.

By the end of January 1945, the pilots and aircrews of Air Group Eleven claimed the following:

- 105 enemy planes shot down

- 272 planes destroyed on the ground

- over 100,000 tons of enemy shipping sunk

- over 100 Japanese ships damaged

These great accomplishments did not come without a price. In four months of flying, CVG-11 lost over 50 aircraft and had more than 60 men killed, missing-in-action, or wounded. Air Group Eleven was replaced by Air Group Seventeen in February 1945 but were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for their service and record.

akfast, lunch, and dinner.

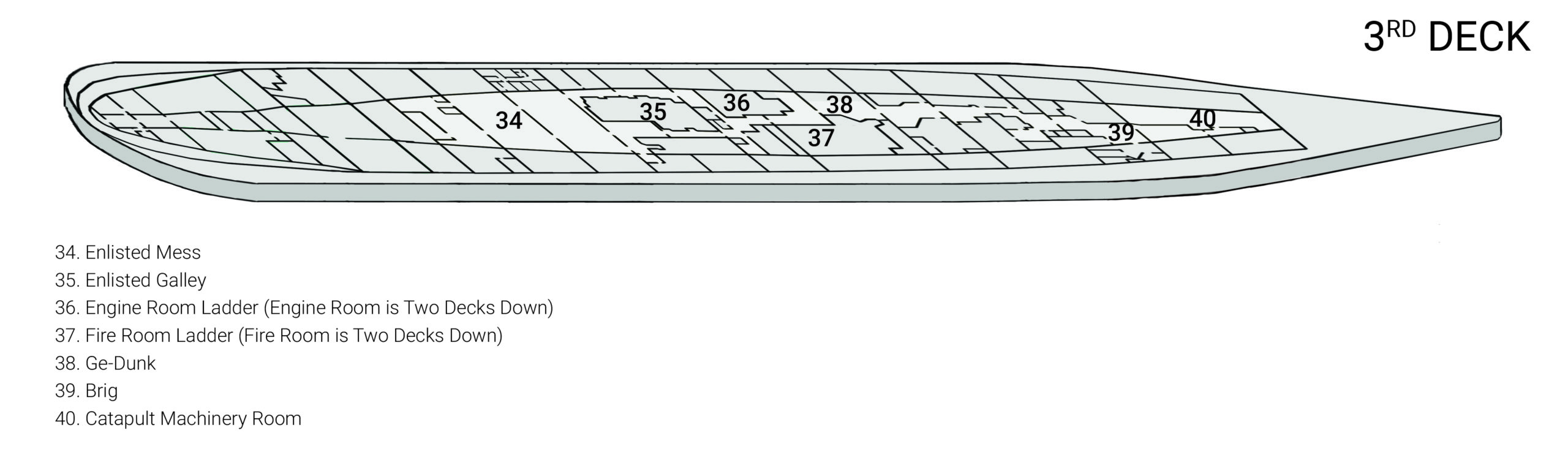

Third Deck

USS Hornet’s 3rd Deck was perhaps more utilitarian but also features wider passageways than the 2nd Deck above. This was, in part, because it was mostly dedicated to the enlisted sailors aboard the ship who made up approximate 2/3 of the ship’s crew! It also leads down into the ship’s Engineering spaces like the Engine and Fire Rooms. See the end of this section for current and historic images of this deck!

34 & 35. Enlisted Mess & Galley

The Enlisted Mess served 4 meals a day: Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner, and Midnight Rations. This was built-in to feed the enlisted crew no matter what shift they were assigned. With so many mouths to feed, the mess crew were producing approximately 10,000 servings of food a day! They used oversized kitchen equipment to get the job done–massive soup pots, ladles the size of whole bowls, and stand mixers as large as most people’s oven!

The Galley had a Bakery nearby who produced bread, doughnuts, pastries, pies and more for not only USS Hornet but also all the other ships that sailed with her in her battle group (smaller ships usually did not have bakeries of their own)! Cakes meant to feed the whole crew easily took up entire tables but were popular for ship moral.

36. Engine Room

USS Hornet has two Engine Rooms, one of which has been fully restored by the museum. Each Engine Room has two Main Engines and associated machinery, for a total of four total. Each Main Engine has two completely separate turbines working in unison, and jointly connected, through a single set of reduction gears, to a single Propeller Shaft. There are four propellers that drive the ship.

Each Engine can produce 37,500 Shaft Horsepower. Starboard engines (1&2) turn clockwise, and port engines (3&4) turn counterclockwise. The four engines produce 150,000 HP in total, and the Turbines turn at approximately 5,000 RPM at full power.

The ship typically only ran two of its engines at any one time while the others were serviced but it could run all four engines if it were trying for top speed, which was 33 knots, or approximately 38 mph.

37. Fire Room

There are eight Babock & Wilcox separately-fired superheated boilers situated in four Fire Rooms, two per Engine Room. They produce saturated and superheated steam — saturated (auxiliary) steam for auxiliary machinery, heating, etc., and superheated (main) steam that traveled into the Engine Rooms at 600 psi and 850 degrees Fahrenheit for use in the main engines and main generators. It was HOT working down there, about 30 degrees hotter than the temperature outside!

Fire Rooms 1 and 2 supplied the forward engine room for Engines 1 and 4, while Fire Rooms 3 and 4 supplied the after engine room for Engines 2 and 3. Each Fire Room and Engine Room is an isolated, self-contained, watertight compartment. Each of these rooms has two levels — upper and lower. All boilers and engines can be inter-connected in case of damage to any one or combination thereof.

38. Ge-Dunk

The 3rd Deck was almost entirely devoted to living spaces and spaces for Personal Services of the enlisted crew. Examples of Personal Services are the Barber Shop, one of the Ship’s Stores for the enlisted crew, and a snack bar called Ge-Dunk. While sailors ate for free at the enlisted mess, they had to pay for their food at the Ge-Dunk but it was open all day and offered different options such as hot sandwiches, hot dogs, ice cream, candy bars, and other types of easy food. It was considered to be an easy, place to stop by and grab a bite to eat and was popular among the crew. There are a few legends for the origin of the name “Ge-Dunk,” but one favorite is that it was introduced in ships originally as an early vending machine and the coins used made a ge-dunk sound.

39. Brig

The ship’s Brig, or its jail, was managed by the Marine Detachment, who acted somewhat as the ship’s police force. It’s small with only 13 beds available, but it was meant to send a message quick. Only the Captain could assign Brig time and the reasons for it were a) if a sailor put the crew in danger or b) if a sailor put the ship in danger. Worse offenders would have been flown off to be tried and jailed on shore but sailors could be assigned to the Brig just overnight to up to two weeks. The Captain could also assign them to just bread and water for the first three days of their stay.

Prisoners in the Brig were expected to wake up at 4:30 AM and do hard labor during the day. When out of their cells, they were chained together and led through the passageways by a Marine. Others in the area would have to turn away to socially isolate them as part of the punishment. The point of the Brig was to make it a terrible time. With approximately 3,500 men, and an average age of 19, a quick but tough punishment for offenses was used to keep order.

40. Catapult Machinery Room

USS Hornet used two H-8 hydraulic catapults on their Flight Deck to launch aircraft. The machinery that powered those catapults were located far below in two machinery rooms. One is on the Third Deck and about a mile of cable run between it and the Flight Deck. Each catapult room has four high-pressure air tanks and one hydraulic fluid tank which connects to a large piston. When an airplane is ready to fire, high-pressure air is piped into the hydraulic fluid tank. A switch is flipped, and that hydraulic fluid threw the piston forward. The piston worked on a 1:10 ratio with the catapult on the Flight Deck–for every foot that the piston moved forward, the plane attached to the catapult on the Flight Deck moved ten feet forward.

Things to Do

Interactives and Entertainment options from the Museum’s Exhibits and Programs ready to Download for at-home use!

For questions or concerns, please email info@uss-hornet.org